123RF

In response to this post, identify the members of your group and what you currently think your unifying theme will be. Only one post is needed for each group. Please respond before noon Thursday, April 17.

123RF

In response to this post, identify the members of your group and what you currently think your unifying theme will be. Only one post is needed for each group. Please respond before noon Thursday, April 17.

HUMAN

Near the end of HUMAN Volume 3, Argus says,

Don’t you have an easier question? The meaning of life. . . Sometimes I think of a phrase I heard as a boy, a friend who said, “Life is like carrying a message from the child you were to the old man you will be. You have to be sure that this message isn’t lost along the way.”

I often think of that because, when I was little, I used to imagine fine things, to dream of a world without beggars in which everyone was happy—simple, subtle things. But you lose those things over the course of life. You just work to be able to buy things, and you stop seeing the beggar, you stop caring.

Where’s the message of the child I once was? Maybe the meaning of life is making sure that this message doesn’t disappear.

If you had to come up with a single message from yourself as a child that is worth carrying with you to yourself as an older person, what do you think it would be?

Compose a post on your group blog in which you answer this question and reflect on the following as you do so:

Imagine yourself at 50, What will be the main preoccupation of your life then? Do you think you will be able to keep this message alive?

What does this message say about you as an individual? friend? partner? citizen?

Comment on the post of at least one other person of the blog you are designated as a commenter for.

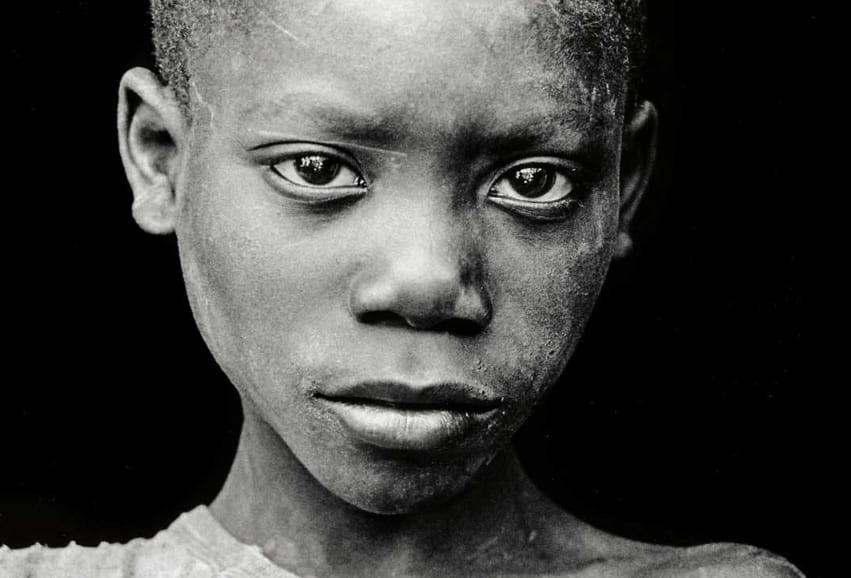

World Vision

Examine the photographs in the attached New York Times feature “Portraits of Reconciliation.” Which one most clearly conveys a genuine spirit of closeness and reconciliation between survivor and perpetrator. Which one least clearly does so. Compare what the two individuals in each pair have to say. On your group blog no later than Wednesday, March 26, compose a post reflecting on what stands out most to your in both the image and what the people have to say about what happened during the genocide and since then.

Rwanda The Sentinel Project

HUMAN

It would probably be easy for many Americans with moderately progressive values to tell Walaa, Brahima, and Frezno what is wrong with their outlook on the proper relationship between men and women. What is more challenging, however, is to attempt a respectful conversation with any of them in terms they might at least partially understand.

HUMAN

HUMAN

On your group blog, address a message to your designated individual, attempting to demonstrate your sincere empathy and respect while also trying to help them to see how their views are problematic in terms they might at least partially understand

It may be helpful to use the transcript below in composing your response.

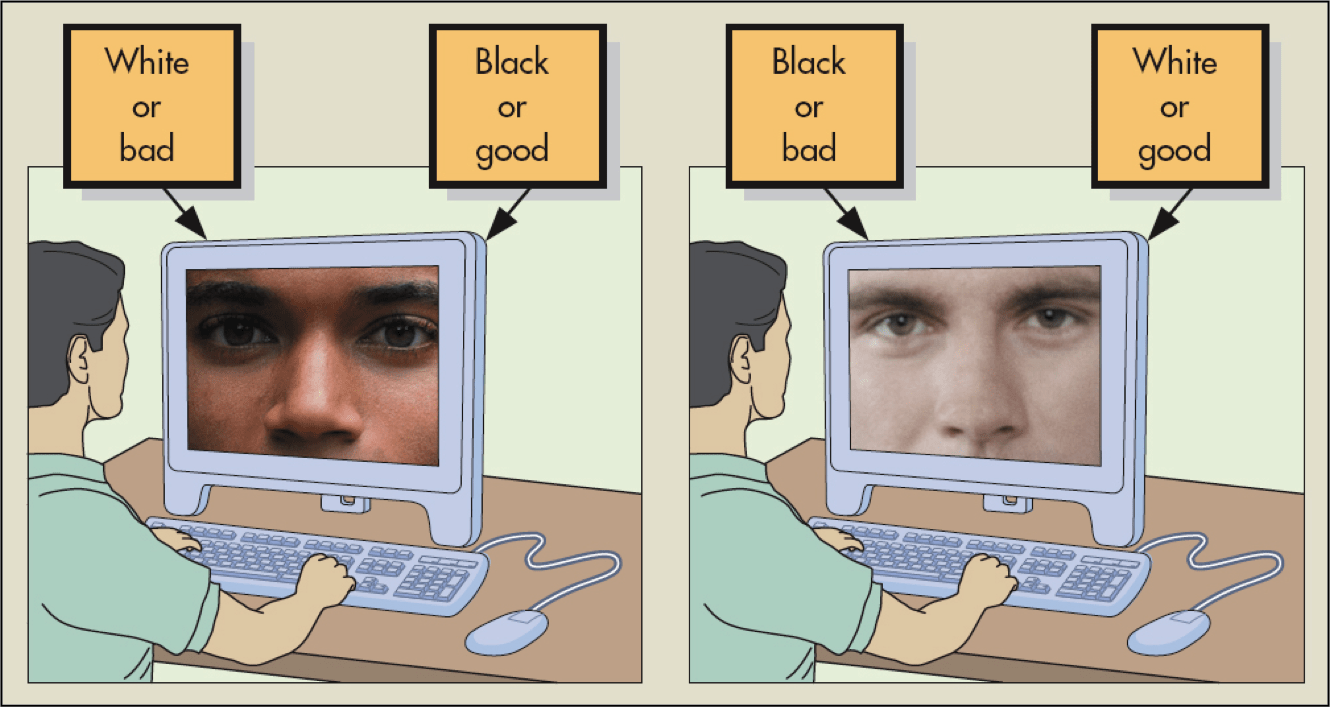

Loyola Marymount University

Follow this link to the guest portal for the IAT. Pick one test and complete the exercise in class. In a reply to this post, describe your experience and whether you learned anything new about yourself. If you are comfortable sharing your results, please include this in your response.

Please choose a different test and compose a second response no later than midnight Wednesday, February 5.

Before class on Thursday, February 6, respond to the class member who responded immediately before you.

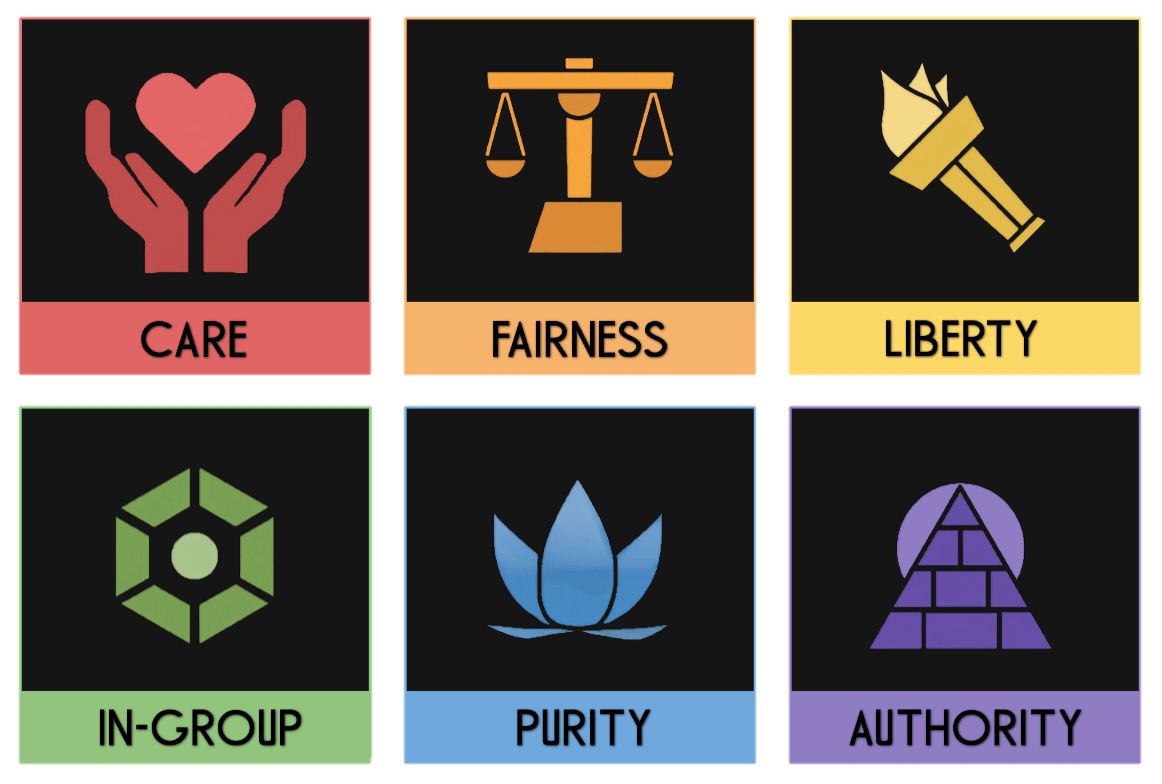

Moral Foundations Test

Open YourMorals.org website, create an account, and complete at least two surveys. One should be the Moral Foundations Questionnaire, and the other should be your choice from among the following: Disgust Scale, the RWA Scale, or the Big Five Personality Scale. When you are done, include in your substantive response to this post which one you completed for your second choice and how meaningful or accurate you believe the results to be.

Villains Wiki – Fandom

As a reply to this post, please do the following:

Alistair Reid, a writer who was also a translator and close friend of Jorge Luis Borges, developed a list of attributes that he believes represent what Borges believed about meaning and language in the context of the idea of fiction.

Alistair Reid, a writer who was also a translator and close friend of Jorge Luis Borges, developed a list of attributes that he believes represent what Borges believed about meaning and language in the context of the idea of fiction.

Working with one or two others, identify parallels between one or more of these attributes (you will find out which in class today) and what you (individually and collectively) feel Yuval Noah Harari means by “fictions” in his chapter “The Tree of Knowledge.”

Dale Richards 2015

Whether you come from somewhere the daily low temperature rarely gets below freezing or somewhere subzero temperatures happen every winter, this was an unusually cold beginning to “Spring” semester 2025. Please describe either (a) something interesting that you did during your semester break or (b) something you are anticipating (with either dread or pleasure) for the weeks ahead.